I picked up Notes from Underground on a slow afternoon thinking it would be a quick, curious read — instead I kept putting it down to argue with the narrator out loud and then picking it back up because I couldn’t stop thinking about certain lines. If you’ve ever read something that makes you uncomfortable and strangely engaged simultaneously occurring, you’ll know the tug this book has.

Below I’ll share the parts that stayed with me, the moments that felt awkward or brilliant, and why those reactions mattered. I’m not retelling the story here,just offering what landed (and what didn’t) from a real reader’s point of view.

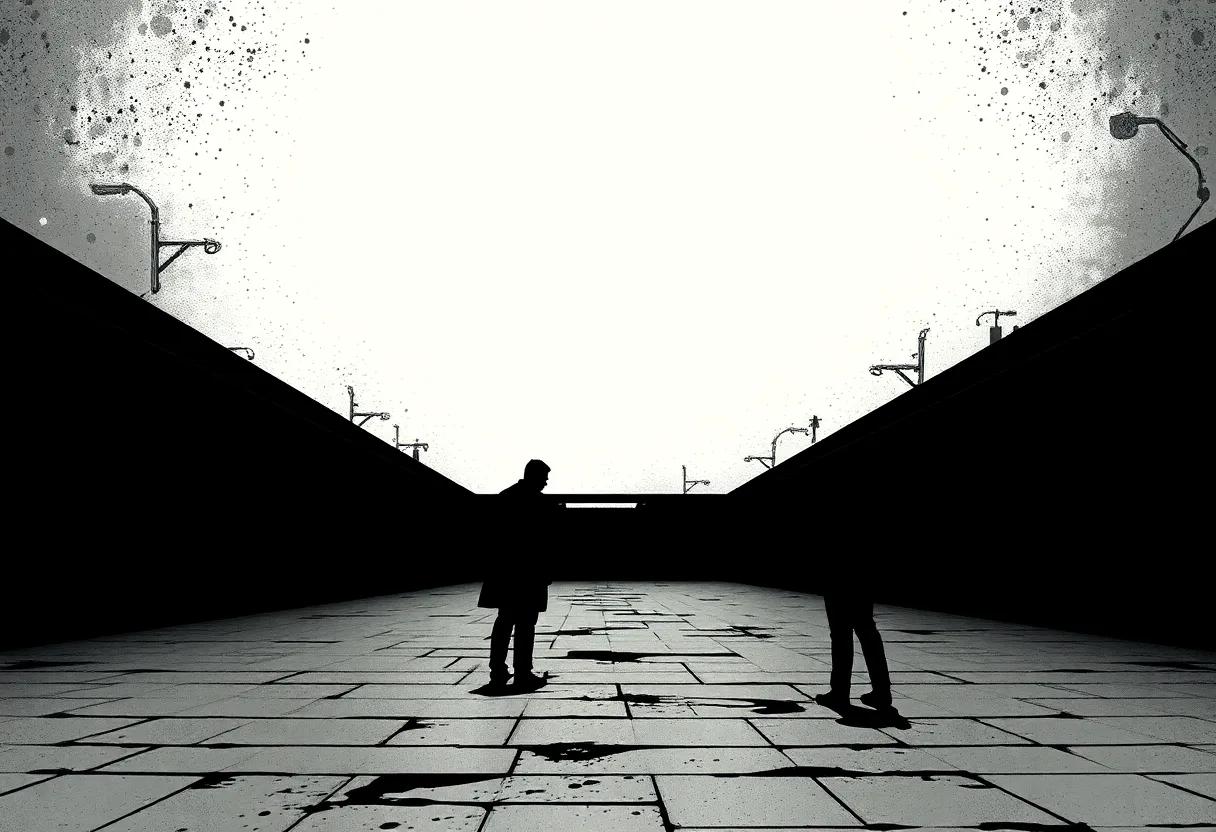

The claustrophobic diary voice that drags you into a cramped Saint Petersburg room

I finished the book feeling like I’d been shut into a tiny room with someone who refuses to look away.The narrator’s tone is relentlessly intimate — a claustrophobic diary that leans in, confesses, sneers, and then confesses again. His petty malice and sudden candor make him disturbingly alive; I found myself both repelled and oddly protective. Sometimes the monologues drag,looping through the same grievance until you start to measure breaths,but those very loops are part of the pressure,the way the voice builds and tightens around you.

Best-Selling Books in This Category

Saint Petersburg here is not a backdrop so much as a set of sensations: damp wallpaper, the thin light through narrow windows, the stink of a shared room and stale tobacco. Those small, claustrophobic details keep pulling your attention back to the speaker’s chest — you can hear his impatience, his shame, his small triumphs. If the pacing falters in places and the narrator’s posturing can feel performative,it doesn’t ruin the effect; instead,it makes the whole thing feel like surviving someone else’s feverish confession,and you leave oddly companionable with a man you wouldn’t invite in.

How spite and stubbornness shape the narrator and create awkward tension at every turn

Reading him feels like sitting across from someone who insists on poking a bruise just to hear you flinch. His spite isn’t theatrical — it’s petty, close-up and tireless — and his stubbornness shapes every choice he makes, often against his own interest. I found myself alternately exasperated and captivated: annoyed at how deliberately he ruins chances for kindness, yet unable to look away because the awkwardness he manufactures is so complete it becomes almost artistic.

Those moments of tension pile up into a kind of social claustrophobia; small scenes become electric with embarrassment. A few things that kept making me wince were:

- his refusal to accept a compliment and then insisting he was right to refuse it,

- intentional grating remarks at the worst possible moments,

- and confessions that felt like self-sabotage offered as performance.

At times the relentless internal monologue drags, and I wanted a break from the loop of spite, but mostly the discomfort is the point — it forces you to sit with someone who won’t relent, and that stubborn refusal to be likeable is what makes his world so painfully, memorably awkward.

The split life structure between ranting monologue and reflective memory scenes in the text

Reading feels like being trapped in a small room with a man who alternates between throwing plates at the walls and telling me about the wallpaper pattern. The ranting sections hit with a raw, bitter energy — full of sharp sentences that feel almost performative, like someone daring you to disagree. Those moments can be exhausting; I occasionally checked my watch, annoyed at the relentless self-flagellation. Yet the memory scenes pull the air back in: quieter, oddly tender snapshots that let you see where his anger came from. The contrast makes him less of a figurehead for an idea and more of a painfully inconsistent person.

The split life structure gives the book a strange rhythm that kept me on edge and, at times, oddly comforted. Memory undercuts rant and rant exposes how vulnerable his memories really are; together they make him unreliable but recognizable. I found myself responding in three ways:

- irritated by repetition in the longer tirades,

- moved by the small domestic humiliations in his recollections, and

- curious enough to keep reading despite the discomfort.

It’s not always tidy — sometimes the shifts feel abrupt — but that jagged pairing is also where the book’s power lives: the voice is abrasive, the memories humane, and the collision between them sticks with you.

The dark humor that wells up in bitter passages and makes the grim readable and odd

There are moments when the bitterness flips into something almost comic, a sudden, dry laugh that cuts through the despair. The narrator’s rants and small cruelties read like a performer sharpening a joke on himself: his self-hatred becomes a kind of dark punchline, his moral stubbornness so extreme it circles back to absurdity. I found myself smiling at lines that should have made me recoil; the book is full of those weird little asides that make the grim strangely readable — you feel you’re in on a private, uncomfortable joke he insists on telling again and again.

That humor doesn’t soften the book’s bite, it complicates it. It lets you stay with the narrator without agreeing with him: you can laugh and then immediately wince. Sometimes the repetition and his passive cruelty drag, and the laughs feel like brief relief rather than relief enough, but more frequently enough they make the darkness feel human and oddly affectionate — the sort of mirth that comes from recognizing someone’s ridiculousness even as you pity them. It left me with mixed feelings: amused, unsettled, and curiously attached to a voice that wastes no chance to mock itself.

small brutal moments that reveal deeper questions about freedom responsibility and choice

There are so many tiny, brutal flashes in the book that stopped me cold — a sudden insult, a calculated humiliation, a petulant refusal of a kindness — and each one felt like a private experiment in what it means to be human. The narrator constantly chooses the ugly option as if to prove something about freedom,and the effect is almost theatrical: you watch a man insist on pain rather than accept a soft hand,as though yielding would make him less himself. It’s easy to be angry with him, but more frequently enough I found myself oddly sympathetic; those petty cruelties read like terrified stabs at autonomy, and they turned abstract questions about responsibility into things you feel in your chest.

Part of me admired how small scenes — the drunken dinner where he baited his former comrades, the awful tenderness he managed toward Liza before humiliating her, the moments he deliberately does the counter-rational thing just to prove a point — strip beliefs down to raw choices. At times his confessions feel long-winded and the monologues stall the pace, but when the book gets to one of those sharp, mean little acts it becomes electric: suddenly you’re not debating ideas, you’re asking yourself what you would do in a split second. Those moments never let freedom, responsibility and choice stay neat; they make them messy, immediate and a little unbearable.

The physical atmosphere of Petersburg with frost covered windows narrow stairwells and lamps

Reading the book, I kept returning to that image of the city seen through frost-covered windows — not the romantic, wide-angled view of a postcard, but a scratchy, fogged membrane that muffles sound and intention. The light that slips through is gray and secretive, revealing faces and street-edges in fragments. I pictured breath fogging the glass, small hands pressed to panes, and felt the distance between people sharpen into a physical chill; the city outside is visible but almost unfairly remote, as if warmth and connection had been left behind on the other side of the pane.

The interior scenes are no softer: narrow stairwells that feel like arteries, carrying characters up and down social ranks, and lamps that throw small, unreliable pools of light — comfort that is always on the verge of failing. Walking those steps on the page makes you feel boxed in but strangely alive, like wandering a maze whose walls whisper the book’s complaints. sometimes the relentless closeness wears on you — a few passages linger longer than I wanted — yet mostly the cramped, lamp-lit world pulled me toward the narrator’s mood and left me noticing the city as a living, uneasy presence.

Translation choices that alter tone making wry contempt readable or blurrier depending on edition

Reading Notes from Underground in different English editions felt oddly like overhearing the same man in rooms with different acoustics.In one translation his bitterness snaps and slyly scalds — the sentences come short, the interjections land with a pathetic, funny fury, and I could almost hear him sneer. In another, the same lines become more measured, the edges softened by genteel phrasing; that wry contempt is still there, but it sits back behind a polite gloss and reads a bit blurrier. as a reader I found my sympathy, my irritation, even the comic timing of his confessions shifting with those choices, making some editions feel immediate and raw and others more reflective and distant.

So if you plan to read it more than once, I’d treat the edition like a lens: pick one that keeps the jagged rhythm if you want the narrator to feel uncomfortably alive, or a smoother version if you prefer to lean into his ideas rather than his voice. Small things make the difference for me — the retention of abrupt exclamations, colloquial turns of phrase, and short, breathy sentences tend to preserve his edge; expanded clauses and genteel wording tend to tame it. I noticed occasional clunky phrasings in the rawer translations and a few slow patches in the smoother ones, but both kinds are worth trying depending on whether you want to be provoked or ponderous company with the Underground Man.

How the book feels like a provocation aimed at polite beliefs and comfortable moral stories

Reading it felt like being politely invited to tea and finding a man who keeps poking at the tablecloth until the whole place is awkward. The Underground Man delights in undoing neat moral stories: he confesses spite instead of sorrow, chooses humiliation over honor, and seems set on proving that our well-meaning explanations for behavior are often cover stories. That constant corrosive voice is less a reasoned argument than a deliberate assault on moral complacency — it makes you want to defend your gentle beliefs and then feel embarrassed about how easily you do it.

I laughed, I flinched, and I kept thinking of people who would close the book in irritation. At moments his ranting feels repetitive and his bitterness tires, but those flaws are also part of the tactic: the book wears you down in the same stubborn way its narrator refuses to be neatly redeemed. if you’re looking for comfort, you won’t find it; if you’re willing to be unsettled, it forces a useful, uncomfortable self-check — the sort that’s rare in polite conversation but oddly necessary.

Dostoevsky himself in shadow and light as reflected in the angry anonymous narrator

Reading the Underground Man feels like catching a glimpse of Dostoevsky himself through a cracked mirror — half revelation, half concealment. The narrator’s fury and petty malice are so naked that I kept wondering where the character ended and the author’s restless curiosity began.At times his rants are exhausting, circling the same grievances, but those repetitions also let you feel the rawness beneath: a kind of stubborn honesty that refuses easy consolations. I found myself oddly grateful for the discomfort; it made Dostoevsky’s compassion — when it surfaces — hit harder as it truly seems almost accidental, slipping through the cracks of a voice that prefers mockery to mercy.

Some specific echoes made the connection between author and narrator hard to ignore:

- an insistence on moral awkwardness rather than tidy answers

- a dark, sometimes bitter humor that undercuts solemnity

- moments of sudden tenderness that feel too intimate to invent

Taken together, these traits painted Dostoevsky in both shadow and light for me: brilliant and unsparing, tender and cruel. The effect isn’t always comfortable — the narrator can be maddeningly self-absorbed — but it left me with a clearer, messier sense of the man behind the pages, someone who delights in contradiction and refuses to be politely understood.

Echoes from the Underground

Reading this piece feels like lingering in a cramped, honest conversation—sharp, uneasy, frequently enough discomfiting, yet arduous to walk away from. The voice stays close enough to be intrusive, and that proximity makes the experience strangely intimate.

Certain sentences keep returning after you’ve closed the book; they prick at assumptions and resist tidy moral closure. The emotional aftertaste is less about resolution than about being unsettled into thought.

For readers who enjoy being provoked rather than comforted,the book offers durable provocation: not answers,but a persistent invitation to revisit lines,questions,and the discomfort they leave behind.