I admit I opened The Golem expecting a spooky period piece and ended up unsettled in a way I didn’t anticipate. The first chapters pulled me in with odd, specific details about Prague and characters who felt both familiar and off-kilter — it made me slow down and pay attention in a way modern thrillers rarely do.

Reading it was a series of small revelations: sentences that demanded a second look, passages that lingered after I put the book down. If you like books that make you rethink a city or keep nudging you back into the text, this one will likely do the same.

Moonlit cobblestone streets of Prague where uncanny figures emerge in foggy light

Walking those moonlit Prague streets with Meyrink felt less like following a plot and more like being pulled along by the city’s breath. The cobblestones gleam under a fog that eats the edges of lantern light, and shadows take on a life of their own—half-peopel, half-omens—stepping out and then folding back into the mist. I found myself pausing between paragraphs as if listening for footsteps: the quiet clack of heels, a distant bell, the metallic scrape of a cart. Small sensory moments kept the world vivid for me:

Best-Selling Books in This Category

- the chill that seemed to seep through the page

- a smell of riverweed and coal

- faces half-lit, then gone

These details made the uncanny feel immediate rather than rhetorical.

At times the pace slackened—Meyrink’s digressions into dream logic can tangle the momentum—but those lulls also let the atmosphere do the work. Instead of clear villains or tidy resolutions, what stayed with me were impressions: the city’s patience, a sense that superstition and everyday life share the same pavement, and how anonymity can be as menacing as any named threat. I sometimes wished for firmer bearings, yet I also enjoyed how the uncertainty left images lingering long after I closed the book—prague as a living, breathing maze where every corner might hide a story or a ghost. Unsettling, yes, but in a way that kept me turning pages to see which shape would step into the lantern light next.

The golem as a hulking clay silhouette in a candlelit alley beside an ancient synagogue

That image — the hulking clay silhouette standing mute in a narrow, candlelit alley beside an ancient synagogue — stayed with me long after I put the book down. Reading those pages felt like walking through a painting: the wet earth smell, the soft scrape of clay against cobbles, and the candles throwing frantic shadows on old stone all pressed in on me. At times the scene is frightening in a low,steady way; at others it felt almost protective,as if the golem were a clumsy guardian who had wandered out of legend and into the wrong century.

What surprised me was how personal that image became — not just a spectacle, but a mood that shaded the rest of the book. I did get impatient with a few slow stretches and some deliberate ambiguity that left me wanting firmer answers, yet the payoff was the atmosphere: a city that feels alive with memory and superstition, and a figure that embodies both threat and sorrow. The alley and the synagogue, candlelight and clay, keep returning to me whenever I picture Prague now.

A dreamlike interior full of dusty books, tarot cards, and a mirror reflecting Prague fog

Reading those passages felt like slipping into a secret room hung with the city’s breath: rows of dusty volumes, tarot cards fanned across a table as if mid-reading, and a tall mirror that never gave back a clean reflection but instead caught Prague fog and a face out of sequence. I kept imagining fingers tracing the cracked leather spines and the faint burn of candle smoke — the book makes you move slowly through space, listening for creaks and half-remembered chants. At moments the atmosphere is so dense it becomes a character of its own, warm and claustrophobic, intimate enough that I felt the book was inviting me to decode someone else’s dream rather than follow a tidy plot.

the cluttered interior acts like a map of the novel’s obsessions: identity folded into ritual, memory stuck in old paper, the city pressing in from outside the panes. Small details kept returning to me afterward:

- a torn tarot card with its corner smoothed by thumb

- marginal notes in a hand that might have been pleading

- a mirror clouded not by steam but by time

Sometimes those sensory passages meander longer than I wanted, and the rythm can slow to a crawl, but I found that lingering in the dust was how the book did its work — it didn’t hand over answers, it made the room stay with you.

Street vendors and shadowy figures trading secrets under gas lamps on misty riverbanks

Walking through those passages felt like eavesdropping on the city’s private life. Under the gas lamps the vendors hawked trinkets and herbs as if they were bargaining with time itself, and figures half-hidden in the fog traded more than money — I kept wanting to lean closer to catch a stolen name or a promise. The prose turns ordinary street noise into something intimate and dangerous: the clink of coins becomes a metronome for gossip, footsteps on the cobbles read like signals, and the river’s breath pulls at the edges of whatever light there is. Meyrink makes Prague feel alive in a way that’s almost claustrophobic; every corner seems to hold a confession or a trick, and I loved how the city’s small details build a network of whispered meanings.

Those scenes stayed with me longer than some of the plotlines; they’re the book’s nervous system, full of suggestion and mood. On the downside, the lush atmosphere sometimes slows things — I occasionally wanted the story to push forward rather than linger in another smoky exchange — and a few moments felt deliberately obscure where I wished for firmer footing. Still, the price is small: the reward is a string of moments that make Prague feel like a living fable, where mist, lamp-glow and rumor are as vital as any named character.

A jittery narrator lost between dreams and waking with a city that feels alive and sly

I kept feeling tugged awake and shoved back into a dream by a voice that trembled with nerves and cigarette smoke. The narrator’s mind is a restless thing—half-remembered names, sudden jolts of paranoia, and images that dissolve just when you think you’ve caught them. it made reading feel like walking down a dim staircase: every step reveals something new and a little dangerous. At times the jitteriness becomes a bit much and I lost the plot for a page or two, but more often it pulled me deeper into a state of delicious unease; I found myself listening for footsteps in my own apartment long after I closed the book.

Prague in meyrink is not a backdrop so much as a living, sly companion. Streets breathe, doorways grin, and the city seems pleased to keep its secrets—sometimes by offering a clue, sometimes by misdirecting you with a wink. I loved how small details—a clatter of tram rails, a shoplight reflected in puddles—felt charged, like little conspiracies between reader and place. The effect isn’t always tidy: the slyness can be maddeningly evasive and a few scenes drag under their own fog. Still, when the mood hits, the city is alive in a way that’s both unsettling and magnetic, and I was happy to be lost in its company.

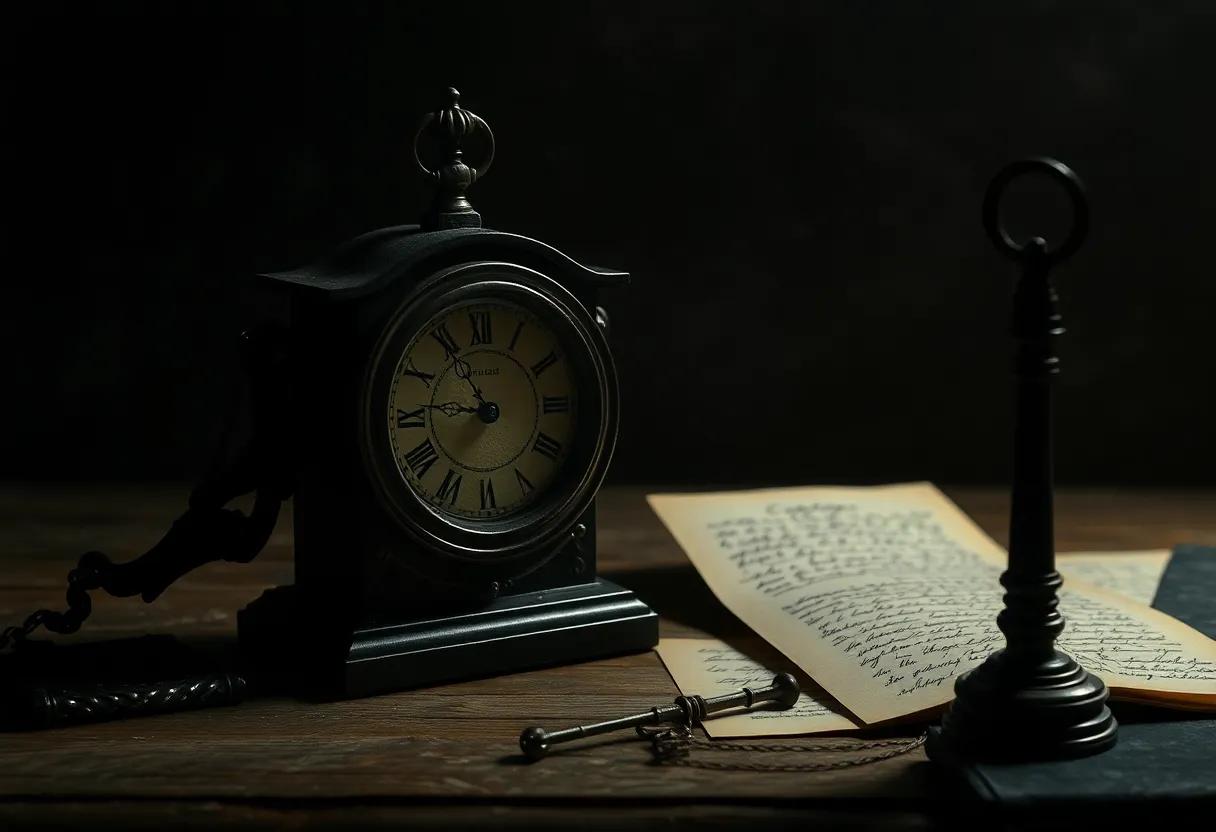

Symbolic objects photographed as relics a clock, a key, a page of cryptic handwriting in dim light

I kept seeing Meyrink’s little props as if they had been lifted out of a dusty attic and put under glass: a battered clock with its hands stubbornly circling an unreadable hour, a cold iron key that promises entrance to rooms you can’t name, and a single torn page of cramped, cryptic handwriting caught in a cone of dim light. These images arrive like snapshots — small, insistently tactile moments that stop the book and let the city breathe. Sometimes those pauses felt like deliberate slowing of the plot (a touch frustrating when I wanted answers), but more often they worked as windows, making the streets and alleys of Prague feel haunted by petty reliquaries and private histories.

Reading those objects felt intimate, like holding other people’s memories and trying to guess the story behind them. They pulled different reactions from me:

- the clock: a vertigo of repeated hours and the sense that time in the book is elastic;

- the key: a quiet dare, a promise of thresholds both literal and psychological;

- the handwritten page: a voice that resists translation, leaving me both intrigued and unsettled.

At the end of a chapter I would find myself lingering on those relics, imagining Pernath or some shadowy stranger turning them over in their hands — small objects that keep the novel’s mysteries tactile even when its logic remains slippery.

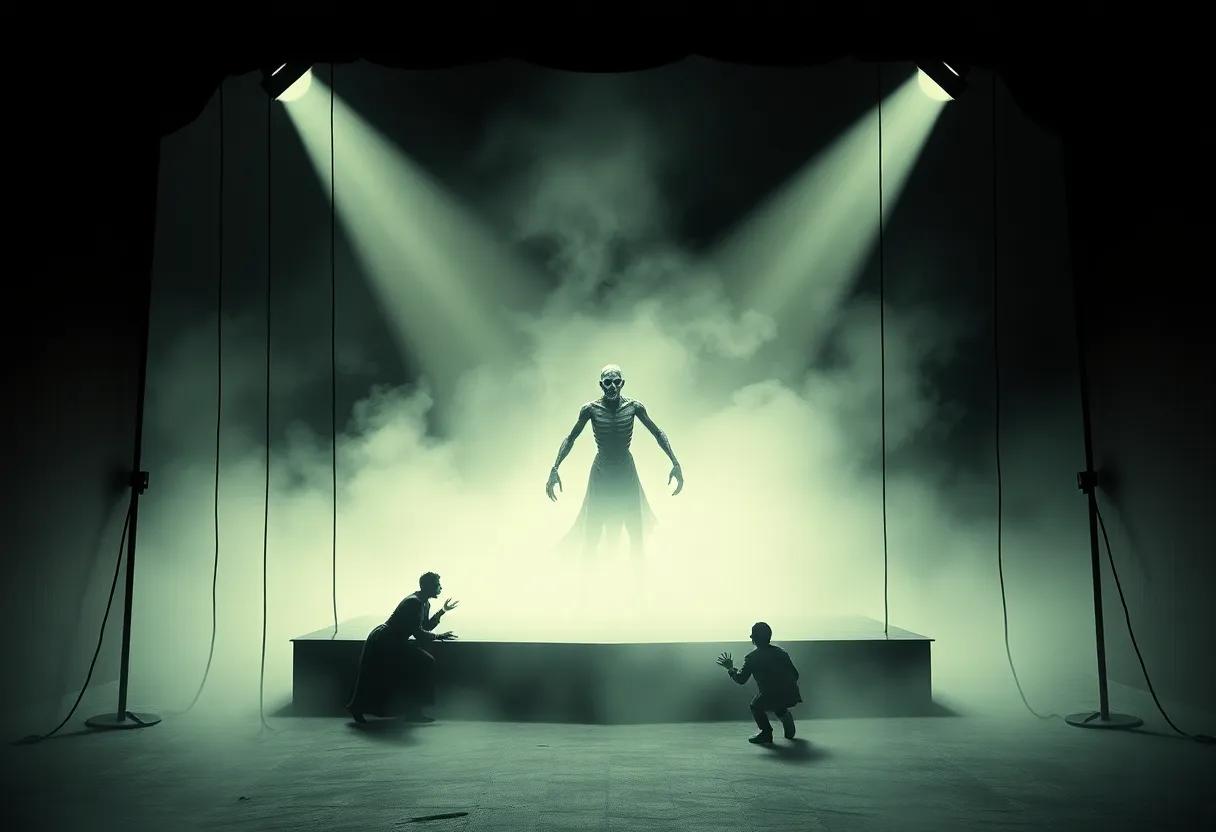

The novel’s eerie humour pictured as a crooked puppet show on a fog drenched stage

Reading Meyrink felt less like following a linear plot and more like being planted in the front row of a strange theater where everything moves a beat behind human expectation. The laugh-out-loud moments are rarely warm — they’re brittle, nervous chuckles that come from watching odd little figures go through ritualistic motions under a haze of streetlamps and mist. Those characters are almost marionette-like: their gestures are exaggerated, their lines deliver a comic sting, and the humour makes the uncanny parts sharper rather than softer. I often caught myself smiling and shivering at the same time.

The effect comes from small, repeated tricks that keep the tone off-kilter:

- quirky, clipped dialog that sounds rehearsed;

- grotesque personalities who behave as if pulled by invisible strings;

- a cyclical, stagey rhythm to scenes that turns eeriness into dark comedy.

sometimes the comic beats feel uneven — a joke lands anachronistically or a mood shift is abrupt — but those imperfections only reinforce the feeling of watching a surreal performance.For me, the book’s oddball humour became one of its most pleasurable qualities, a constant companion that made Prague feel like a theatre I couldn’t quite trust or look away from.

The Prague Jewish quarter rendered in sepia tones with alleyways, synagogues and ornate signs

Reading Meyrink’s prague felt like leafing through a weathered photograph tinted in sepia: alleyways narrow into shadows, synagogue domes tilt like remembered faces, and wrought-iron signs hang with the stubborn dignity of things that have outlived their makers. I kept wanting to reach out and touch the cobbles, as if the book itself had texture—soft, dusty, slightly brittle. The details are small and stubbornly specific, which made me feel less like a spectator and more like a trespasser guided down corridors that hold their own slow, private logic.

The people and the city blur into one another; a shopkeeper’s cough, a prayer murmured behind a shutter, and the mechanical hum of a city that remembers itself all coalesce into an uneasy comfort. At times the prose is so elliptical that I slowed to untangle sentences—occasionally frustrating, but frequently enough fitting, as if the book preferred secrecy to clear clarification. If you like wandering through atmosphere more than crisp plot turns, the sepia-clad Prague here is a place you’ll want to return to, even when the fog makes you lose your way.

Gustav Meyrink as a shadowed figure in a windowed study surrounded by occult books and maps

Reading Meyrink feels at times like standing on the other side of a frosted window, watching a figure bend over a cluttered desk while rain traces slow lines down the glass. The author becomes that shadowed presence: part storyteller, part occult landlord of Prague’s back alleys. His study is crowded with the smell of old paper and a chaos of maps and grimoires; I could almost see the light fall across a globe, the corner of a map pinned with a thumbtack. Those details made the city feel less like a setting and more like a living room where secrets are casually discussed over tea — intimate, unsettling, and oddly domestic.

At moments the book held me to that window,mesmerized by the hush and the suggestion that someone inside is rearranging the world for their own amusement. At other times the pace faltered under digressions into lore or repetitive atmosphere-building; a few chapters lingered too long in the study while the streets begged for attention. Still, the mixture of curiosity and mild unease is what stayed with me most: the sense of being both welcomed and warned. Small things kept resurfacing in my mind after I closed the book — candle-dripped maps, a brass key, a smudge on the sill — tiny anchors to a voice that reads like a confidant in a dimly lit room.

Echoes from Prague’s Labyrinth

Meyrink’s prose guides you through a twilight where streets feel inhabited by memory and myth, and the act of reading becomes a wayfinding exercise between clarity and fog. Time slips; details catch at the edges of comprehension, leaving a sensation of having walked somewhere just out of reach.

The emotional aftertaste is a gentle, persistent unease—images and questions that linger rather than resolve, asking you to return to particular lines or corners of the book.Those lingering fragments take on new shape with each revisit.

This is a book that rewards readers who prefer atmosphere to tidy answers, who enjoy being provoked rather than pacified. It leaves you carrying Prague with you for a while: a mood,a riddle,and an invitation to keep wandering.